References

Abrams P, Artibani W (2004) Understanding Stress Urinary Incontinence. Ismar Healthcare, Belgium

Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al (2002) The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Subcommittee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn 21(2): 167–78

Aziz I, Whitehead WE, Palsson OS, Törnblom H, Simrén M (2020) An approach to the diagnosis and management of Rome IV functional disorders of chronic constipation. Exp Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 14(1): 39–46

Bedoya-Ronga A, Currie I (2014) Improving the management of urinary incontinence. Practitioner 258(1769): 21–4

Beeckman D, et al (2015) Proceedings of the Global IAD Expert Panel. Incontinence-associated dermatitis: moving prevention forward. Wounds International, London. Available online: www.woundsinternational.com

Bliss D, Mimura T, Berghmans B, et al (2017) Assessment and conservative management of faecal incontinence and quality of life in adults. In: Abrams P, Cardozo L, Wagg A, Wein A, eds. Incontinence. 6th edn. Health Publications Ltd, Tokyo

Collerton J, Davies K, Jagger C, et al (2009) Health and disease in 85 year olds: baseline findings from the Newcastle 85+ cohort study. BMJ 339: b4904

Continence Foundation of Australia (2020) Urinary incontinence. Available online: www.continence.org.au/types-incontinence/urinary-incontinence

Daugherty M, Chelluri R, Bratslavsky G, Byler T (2017) Are we underestimating the rates of incontinence after prostate cancer treatment? Results from NHANES. Int Urol Nephrol 49(10): 1715–21

Day MR, Leahy-Warren P, Loughran S, et al (2014). Community-dwelling women’s knowledge of urinary incontinence. Br J Community Nurs 19(11): 534–8

Department of Health (2016) Reducing infections in the NHS. DH, London. Available online: www.gov.uk/government/news/reducing-infections-in-the-nhs

Drossman DA (senior editor), Chang L, Chey WD, Kellow J, Tack J, Whitehead WE and The Rome IV committees (2017) Rome IV Multidimensional Clinical profile for gastrointestinal disorders. Rome Foundation, North Carolina

Gray M, Giuliano KK (2018) Incontinence associated dermatitis, characteristics and relationship to pressure injury: a multisite epidemiologic analysis. J Wound, Ostomy Continence Nurs 45(1): 63–7

Hannestad YS, Rortveit G, Sandvik H, Hunskaar S (2000) A community-based epidemiological survey of female urinary incontinence: the Norwegian EPINCONT study. J Clin Epidemial 53: 1150–7

Haylen BT, de Ridder D, Freeman RM, et al (2010). An international urogynecological association (IUGA)/ international continence society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn 29(1): 4–20

Heath H (2009) The nurse’s role in helping older people to use the toilet. Nurs Standard 24(2): 43–7

Hunskaar S, Burgio K, Clark A, Lapitan M, Nelson R, Sillen U (2005). Epidemiology of urinary (UI) and faecal (FI) incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse (POP). In: Abrams P, Khiry S, Cardozo L, Wein A, eds. WHO – ICS International Consultation on Incontinence. 3rd edn. Health Publications Ltd, Paris: 255–312

Iblasi A, Alqaisiya M, Binkanan A, Itani H (2019) Incontinence-associated dermatitis: a gap in practice. Wounds Middle East 6(2): 6–10

Lennie KH, Clancy B, Westbury J, et al (2020) Urinary incontinence post radical prostatectomy: what men need to know. J Community Nurs 34(6): 52–7

Meng E, Lin WY, Lee WC, Chuang YC (2012) Pathophysiology of overactive bladder. Low Urin Tract Symptoms 4(S1): 48–55

Milson I, Altman D, Cartwright R, et al (2017) Epidemiology of urinary incontinence (UI) and other lower urinary tract symptoms(LUTS), pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and anal incontinence (AI). In: Abrams P, Cardozo L, Wagg A, Wein A, eds. WHO – ICS International Consultation on Incontinence. 6th edn. Health Publications Ltd, Tokyo: 5–141

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2014) Faecal incontinence in adults. Quality standard [QS] 54. NICE, London. Available online: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/QS54

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2015) Urinary incontinence in women. Quality Standard 77. NICE, London. Available online: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs77

NHS England (2018) Excellence in continence care: Practical guidance for commissioners, and leaders in health and social care. Available online: www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/excellence-in-continence-care.pdf

NHS Urinary Incontinence (2019) Urinary incontinence — overview. Available online: www.nhs.uk/conditions/urinary-incontinence/

Norton C, Chelvanayagam S, eds (2004) Bowel Continence Nursing. Beaconsfield Publishers, Oxford

Royal college of Nursing (2019) Bowel Care Management of Lower Bowel Dysfunction, including Digital Rectal Examination and Digital Removal of Faeces. RCN, London. Available online: www.rcn.org.uk

Soliman Y, Meyer R, Baum MD (2016) Falls in the elderly secondary to urinary symptoms. Rev Urol 18(1): 28–32

Yates A (2015) Urinary tract infection in older adults. Nurs Res Care 17(10): 370–3

Yates A (2016) The importance of good continence care for older people. Nurs Res Care 18(10): 535–9

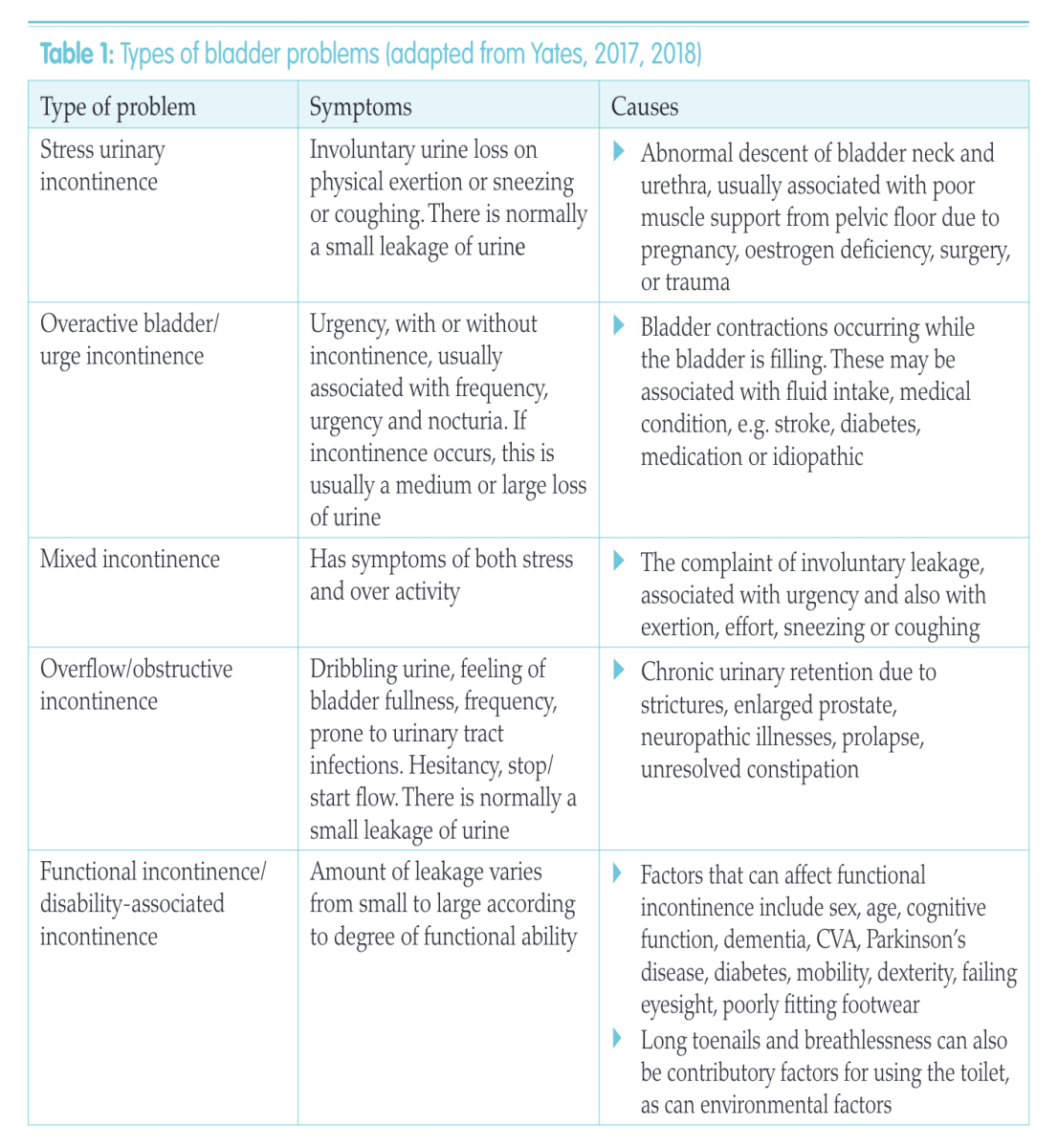

Yates A (2017) Incontinence and associated complications — is it avoidable? Nurse Prescribing 15(6): 288–9

Yates A (2018) How to perform a comprehensive baseline continence assessment. Nurs Times 114(5): 26–9

Yates A (2019) Basic continence assessment: what community nurses should know. J Community Nurs 33(3): 52–5

Yates A (2020) Incontinence-associated dermatitis 1: risk factors for skin damage. Nurs Times 116(3): 46–50

Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al (2002) The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Subcommittee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn 21(2): 167–78

Aziz I, Whitehead WE, Palsson OS, Törnblom H, Simrén M (2020) An approach to the diagnosis and management of Rome IV functional disorders of chronic constipation. Exp Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 14(1): 39–46

Bedoya-Ronga A, Currie I (2014) Improving the management of urinary incontinence. Practitioner 258(1769): 21–4

Beeckman D, et al (2015) Proceedings of the Global IAD Expert Panel. Incontinence-associated dermatitis: moving prevention forward. Wounds International, London. Available online: www.woundsinternational.com

Bliss D, Mimura T, Berghmans B, et al (2017) Assessment and conservative management of faecal incontinence and quality of life in adults. In: Abrams P, Cardozo L, Wagg A, Wein A, eds. Incontinence. 6th edn. Health Publications Ltd, Tokyo

Collerton J, Davies K, Jagger C, et al (2009) Health and disease in 85 year olds: baseline findings from the Newcastle 85+ cohort study. BMJ 339: b4904

Continence Foundation of Australia (2020) Urinary incontinence. Available online: www.continence.org.au/types-incontinence/urinary-incontinence

Daugherty M, Chelluri R, Bratslavsky G, Byler T (2017) Are we underestimating the rates of incontinence after prostate cancer treatment? Results from NHANES. Int Urol Nephrol 49(10): 1715–21

Day MR, Leahy-Warren P, Loughran S, et al (2014). Community-dwelling women’s knowledge of urinary incontinence. Br J Community Nurs 19(11): 534–8

Department of Health (2016) Reducing infections in the NHS. DH, London. Available online: www.gov.uk/government/news/reducing-infections-in-the-nhs

Drossman DA (senior editor), Chang L, Chey WD, Kellow J, Tack J, Whitehead WE and The Rome IV committees (2017) Rome IV Multidimensional Clinical profile for gastrointestinal disorders. Rome Foundation, North Carolina

Gray M, Giuliano KK (2018) Incontinence associated dermatitis, characteristics and relationship to pressure injury: a multisite epidemiologic analysis. J Wound, Ostomy Continence Nurs 45(1): 63–7

Hannestad YS, Rortveit G, Sandvik H, Hunskaar S (2000) A community-based epidemiological survey of female urinary incontinence: the Norwegian EPINCONT study. J Clin Epidemial 53: 1150–7

Haylen BT, de Ridder D, Freeman RM, et al (2010). An international urogynecological association (IUGA)/ international continence society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn 29(1): 4–20

Heath H (2009) The nurse’s role in helping older people to use the toilet. Nurs Standard 24(2): 43–7

Hunskaar S, Burgio K, Clark A, Lapitan M, Nelson R, Sillen U (2005). Epidemiology of urinary (UI) and faecal (FI) incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse (POP). In: Abrams P, Khiry S, Cardozo L, Wein A, eds. WHO – ICS International Consultation on Incontinence. 3rd edn. Health Publications Ltd, Paris: 255–312

Iblasi A, Alqaisiya M, Binkanan A, Itani H (2019) Incontinence-associated dermatitis: a gap in practice. Wounds Middle East 6(2): 6–10

Lennie KH, Clancy B, Westbury J, et al (2020) Urinary incontinence post radical prostatectomy: what men need to know. J Community Nurs 34(6): 52–7

Meng E, Lin WY, Lee WC, Chuang YC (2012) Pathophysiology of overactive bladder. Low Urin Tract Symptoms 4(S1): 48–55

Milson I, Altman D, Cartwright R, et al (2017) Epidemiology of urinary incontinence (UI) and other lower urinary tract symptoms(LUTS), pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and anal incontinence (AI). In: Abrams P, Cardozo L, Wagg A, Wein A, eds. WHO – ICS International Consultation on Incontinence. 6th edn. Health Publications Ltd, Tokyo: 5–141

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2014) Faecal incontinence in adults. Quality standard [QS] 54. NICE, London. Available online: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/QS54

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2015) Urinary incontinence in women. Quality Standard 77. NICE, London. Available online: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs77

NHS England (2018) Excellence in continence care: Practical guidance for commissioners, and leaders in health and social care. Available online: www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/excellence-in-continence-care.pdf

NHS Urinary Incontinence (2019) Urinary incontinence — overview. Available online: www.nhs.uk/conditions/urinary-incontinence/

Norton C, Chelvanayagam S, eds (2004) Bowel Continence Nursing. Beaconsfield Publishers, Oxford

Royal college of Nursing (2019) Bowel Care Management of Lower Bowel Dysfunction, including Digital Rectal Examination and Digital Removal of Faeces. RCN, London. Available online: www.rcn.org.uk

Soliman Y, Meyer R, Baum MD (2016) Falls in the elderly secondary to urinary symptoms. Rev Urol 18(1): 28–32

Yates A (2015) Urinary tract infection in older adults. Nurs Res Care 17(10): 370–3

Yates A (2016) The importance of good continence care for older people. Nurs Res Care 18(10): 535–9

Yates A (2017) Incontinence and associated complications — is it avoidable? Nurse Prescribing 15(6): 288–9

Yates A (2018) How to perform a comprehensive baseline continence assessment. Nurs Times 114(5): 26–9

Yates A (2019) Basic continence assessment: what community nurses should know. J Community Nurs 33(3): 52–5

Yates A (2020) Incontinence-associated dermatitis 1: risk factors for skin damage. Nurs Times 116(3): 46–50