References

Ansell T, Harari D (2017) Urinary catheter-related visits to the emergency department and implications for community services. Br J Nurs 26(9): S4–11

Ansell T, Lawton S, Hopper A (2017) Reducing Harm from Urinary Catheters: A Collaborative Approach in South London. Health Innovation Network, London: 1–31

Allegranzi B, Nejad SB, Combescure C et al (2011) Burden of endemic healthcare- associated infection in developing countries: systematic review and metaanalysis. Lancet 377(9761): 228–41

Chapple A, Prinjha S, Feneley R, Ziebland S (2016) Drawing on accounts of longterm urinary catheter use: design for the ‘seemingly mundane’. Qual Health Res 26(2): 154–63

Cottenden A, Bliss D, Buckley B, et al (2013) Management using continence products. In: Abrams P, Cardozo L, Khoury S, Wein A (eds) Incontinence. 5th edn. European Association of Urology and International Consultation on Urological Diseases, Arnhem, The Netherlands: 1651–1786

Ewbank L, Thompson J, McKenna H (2017) NHS hospital bed numbers: past, present future. The King’s Fund, London

Foley FEB (1937) A hemostatic bag catheter. Journal of Urology 38: 137–9

Getliffe KA (1994) The characteristics and management of patients with recurrent blockage of long-term urinary catheters. J Adv Nurs 20(1): 140–49

Getliffe K, Newton T (2006) Catheterassociated urinary tract infection in primary and community health care. Age Ageing 35(5): 477–81

Gage H, Avery M, Flannery C, Williams P, Fader M (2017) Community prevalence of long-term urinary catheters use in England. Neurourol Urodyn 36(2): 293–96

Health Education England (2015) Antimicrobial Stewardship: Start smart - then focus. HEE, London. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service. gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/417032/Start_Smart_Then_Focus_FINAL.PDF (accessed January 2019)

Hunter KF, Bharmal A, Moore KN (2013) Long-term bladder drainage: Suprapubic catheter versus other methods: A scoping review. Neurourol Urodyn 32(7): 944–51

Khan AA, Mathur S, Feneley R, Timoney AG (2007) Developing a strategy to reduce the high morbidity of patients with long-term urinary catheters: the BioMed catheter research clinic. BJU Int 100(6): 1298–301

Kohler-Ockmore J, Feneley R (1996) Long-term catheterization of the bladder. Br J Urol International 77(3): 347–51

Kunln CM, Douthitt S, Dancing J, Anderson J, Moeschberger M (1992) The association between the use of urinary catheters and morbidity and mortality among elderly patients in nursing homes. Am J Epidemiol 135(3): 291–301

McNulty C, Freeman E, Smith G, et al (2003) Prevalence of urinary catheterization in UK nursing homes. J Hosp Infect 55(2): 119–23

NHS England (2014) NHS Five Year Forward View. NHS England, Leeds

Saint S, Trautner BW, Fowler KE, Colozzi J, Ratz D, Lescinskas E, Hollingsworth JM, Krein SL (2018) A multicenter study of patient-reported infectious and noninfectious complications associated with indwelling urethral catheters. JAMA Intern Med 178(8): 1078–85

Tay LJ, Lyons H, Karrouze I, et al (2016) Impact of the lack of community urinary catheter care services on the Emergency Department. BJU Int 118(2): 327–34

Wagg A, Potter J, Peel P, Irwin P, Lowe D, Pearson M (2008) National audit of continence care for older people: management of urinary incontinence. Age Ageing 37(1): 39–44

Wilde MH, Brasch J, Getliffe K, et al (2010) Study on the use of long-term urinary catheters in community-dwelling individuals. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 37(3): 301–10

World Health Organization. Antimicrobial Resistance. Available online: www.who.int/antimicrobial-resistance/en/ (last accessed 24 January, 2019)

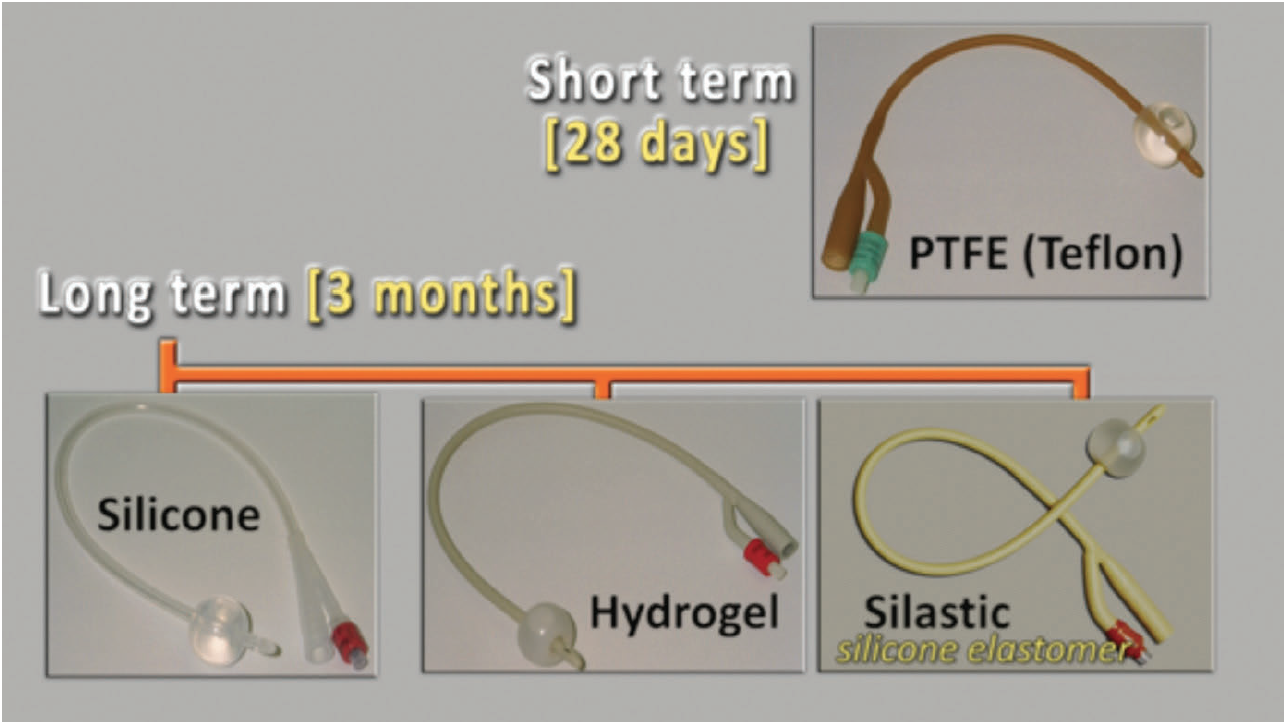

This 11-module programme consists of short, animated lectures delivered in three to four-hour sessions. Six modules deal with core anatomical themes, the fundamentals of material science and the biology of catheter life. The five further sequential modules cover clinical dimensions of catheter care. The aim of the programme is to ‘iron out’ many of the confusions, myths and misunderstandings that surround catheter care.

This 11-module programme consists of short, animated lectures delivered in three to four-hour sessions. Six modules deal with core anatomical themes, the fundamentals of material science and the biology of catheter life. The five further sequential modules cover clinical dimensions of catheter care. The aim of the programme is to ‘iron out’ many of the confusions, myths and misunderstandings that surround catheter care.

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Figure 2.

Figure 2. Figure 3.

Figure 3. The two natural urethral bends in the male urethra are also the most common sites for urethral strictures to occur, as the catheter may rub resulting in trauma. Trauma within the urethral lumen can result in inflammation. As this heals, there is resultant scar tissue leading to contraction and a tighter, more rigid, passage. This is known as a urethral stricture and markedly reduces the lumen size of the urethra. Therefore, the smallest catheter suitable should always be used, thus minimising disruption to the urethral wall and the risk of future development of urethral strictures.

The two natural urethral bends in the male urethra are also the most common sites for urethral strictures to occur, as the catheter may rub resulting in trauma. Trauma within the urethral lumen can result in inflammation. As this heals, there is resultant scar tissue leading to contraction and a tighter, more rigid, passage. This is known as a urethral stricture and markedly reduces the lumen size of the urethra. Therefore, the smallest catheter suitable should always be used, thus minimising disruption to the urethral wall and the risk of future development of urethral strictures. Perhaps the biggest controversy that confuses healthcare professionals is the role of antibiotics in catheter care. The presence of a catheter in the human urinary tract effectively creates a dynamic biological ecosystem. When a catheter is inserted, a muco-protein film begins to develop on its surface — produced by the bladder urothelium. At the same time, bacteria ascend along the catheter and start to colonise the urinary system. Within 24 hours, all catheterised bladders are colonised with bacteria. Therefore, any patient who has had a catheter in place for more than one day will have a positive dipstick test of urine to leucocytes and nitrites. This is not infection, but rather normal colonisation due to the presence of a catheter. It is therefore essential to avoid doing a dipstick on urine from an existing catheter. Antibiotics will never eradicate this bacterial fauna, indeed, the exposure of antimicrobials to this ecosystem will simply clone out antibiotic resistance in a system where microbial colonisation is normal and unchangeable. The course, thus provides guidance on how antibiotic administration should be both limited and used effectively. Messages which are in keeping with the teaching of both the World Health Organization (WHO) and Health Education England (HEE, 2015).

Perhaps the biggest controversy that confuses healthcare professionals is the role of antibiotics in catheter care. The presence of a catheter in the human urinary tract effectively creates a dynamic biological ecosystem. When a catheter is inserted, a muco-protein film begins to develop on its surface — produced by the bladder urothelium. At the same time, bacteria ascend along the catheter and start to colonise the urinary system. Within 24 hours, all catheterised bladders are colonised with bacteria. Therefore, any patient who has had a catheter in place for more than one day will have a positive dipstick test of urine to leucocytes and nitrites. This is not infection, but rather normal colonisation due to the presence of a catheter. It is therefore essential to avoid doing a dipstick on urine from an existing catheter. Antibiotics will never eradicate this bacterial fauna, indeed, the exposure of antimicrobials to this ecosystem will simply clone out antibiotic resistance in a system where microbial colonisation is normal and unchangeable. The course, thus provides guidance on how antibiotic administration should be both limited and used effectively. Messages which are in keeping with the teaching of both the World Health Organization (WHO) and Health Education England (HEE, 2015).